Alumnus's Invention Put Pencil to Paper

By Chris Coughlan-Smith, originally printed in the May-June, 1999, issue of Minnesota magazine.

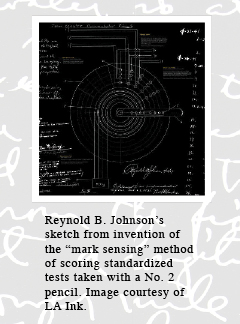

As the school years final set of exams approaches, millions of students are preparing to attack the universal multiple-choice bubble test with sharpened number 2 pencils. How the tests work and why the number 2 pencil is best are not questions foremost in the minds of finals-stressed University of Minnesota students. But one of their predecessors knew the answers to those questions even before the tests existed. Reynold B. Johnson ('29) invented the test-scoring method.

Johnson was a high-school science teacher in Michigan in the early 1930s when he came up with the method and machinery to score tests electronically. Johnson had learned the electrical properties of pencils when, as boys, he and his brother used to rub soft lead pencils over automobile spark plugs, temporarily shorting out the engines. Their favorite targets, he recalled in 1997 when on campus to receive an award, were the Model-Ts owned by their older sisters "gentlemen callers." Johnson's test-scoring machine proved so ingenious and valuable that IBM bought it and hired him.

"The classroom of the future will be as different from today's as the computer center is different from the accounting room with its high stools of a few decades ago."

While at IBM, Johnson developed so many new machines and methods that he eventually held more than 90 patents when he died in September 1998. His most important invention may have been the Random Access Method of Accounting Control, which made the leap from storing data on punch cards to magnetic storage on disks and earned him the reputation of father of the computer disk drive.

His other inventions include a kind of videotape that Sony still uses and children's Talk to Me Books, an idea purchased by Fisher-Price. He received the National Medal of Technology from President Ronald Reagan in 1986.

Students may not care how bubble-tests work, but instructors with just a few days to review tests and turn in grades are glad a University alumnus once figured it out.