About Roy Wilkins

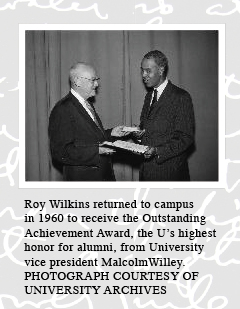

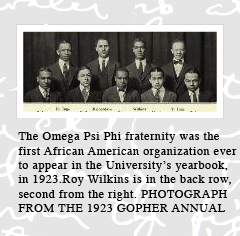

Roy Wilkins was one of the most prominent leaders of the civil rights movement in the United States from the 1930s through the 1970s. Born in St. Louis in 1901, he was raised in St. Paul, Minnesota, by his aunt and uncle. Wilkins graduated from the University of Minnesota with a degree in sociology in 1923.

Wilkins spent 46 years with the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), including 22 as its top executive. During his tenure, the NAACP led the nation into the civil rights movement and spearheaded efforts that led to significant civil rights victories, including Brown vs. Board of Education, the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Wilkins believed that consensus building, dialogue, and pursuit through legal channels were the most effective agents of change for racial equality. In 1967, President Lyndon Johnson awarded Wilkins the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Five years after Wilkins' death in 1981, the Roy Wilkins Foundation, led by his widow, Aminda, approached the University of Minnesota to establish the Roy Wilkins Chair of Human Relations and Social Justice and found a research center devoted to the study of inequality and issues of concern to people of color. The chair and center were to be located at the Humphrey School of Public Affairs. The University and the Wilkins Foundation worked together to raise funds to support the initiative.

In 1992, after a $2 million endowment had been established through the support of corporations, foundations, individuals, and the University, the Wilkins chair and center were formally established.

The Roy Wilkins Center for Human Relations and Social Justice was given the mandate to carry on Wilkins' work through cutting-edge research, dialogue, and consensus among people of all communities.